Jeff Gomez on how stories can shift culture towards collective healing

In The Shift, UN Live's thought leaders explore how music, art, media, and even everyday spaces—from stadiums to dinner tables—can become stages for more connection, inspired empathy, and collective action. In today's Q&A, Katja Iversen, UN Live CEO, speaks with Jeff Gomez, acclaimed writer, producer, and CEO of Starlight Runner Entertainment, on how transmedia narratives and shared story universes can move us from awareness to genuine behavioral change, and from division to collective healing. Read along as he shares how stories like Black Panther and One Piece illustrate paths to transcending conflict, and why the narratives we need must shift us from "me" to "we."

It's time to rethink—and imagine the futures we want to create.

UN Live: You've shaped shared universes that millions inhabit. What, in your view, makes a story powerful enough to shift culture rather than simply entertain it?

Photo: Gomez No Story

Jeff: The popular notion is that great stories convey strong morals or virtues to which we can aspire. To me the greatest stories are the ones that also illustrate the path to understanding. One of the things I do best is to identify these paths of wisdom in the storyworlds that I work with. They are not always obvious and they’re not always complete, but truly transcendent narratives require them.

The ancient Epic of Gilgamesh explored the human condition and helped to shape philosophical thought in subsequent mythologies and religious narratives. Homer’s Odyssey amplified Greek ideals of heroism and honor, influencing Western literary traditions. Tolkien’s Middle-earth stories are a master class for perseverance in the face of overwhelming challenges.

Stories and shared universes capable of moving an entire people contain elements that resonate powerfully with our deepest inner desires. They warn us of our follies but show us a way to transcend them. We see this in the worlds of Harry Potter, One Piece, and Hunger Games. They give us the tools to manage our fears and become productive human beings. They provide us with a ladder comprised of the alternating rungs of education and action.

Stories powerful enough to shift culture resonate with the ancient narratives that connect humanity with the greater universe. They make us feel less alone. They appeal to our need to overcome our fears, to explore life, to have agency, to belong, to be loved—the very desires we experienced when we first emerged from caves. But they must also lend themselves to our sense of drama. They must be powerful enough to be retold across media and in multiple variations. Stories that shift culture must also be rites of passage. My work in Hollywood, video games, and even with sociopolitical narratives is informed by the huge responsibility held by storytellers who speak to tens or hundreds of millions. Sometimes that means better defining those passages, signifying those archetypes and aspirational drivers, revealing those ladders to my studio partners. Sometimes it means building out those rungs.

Once in a while, it means pointing out toxicities, aspects of a story or storyworld that subvert or corrode the narrative’s fundamental messages. Weaponized storytelling has divided and conquered nations. In entertainment, multiple sequels that dramatize the same exact conflict with no enlightenment, no path to reconciliation, are lazy, self-indulgent and wasteful. The audience always tires of this. Sometimes we’re ignored by our clients, and my team is deeply disappointed. The story almost always fades from popular culture as a result.

The greatest stories shift culture by not only providing the audience with the aforementioned ladder but also by inspiring them to climb it, lifting themselves and, collectively, society out of the depths of human strife and conflict.

Photo: Gomez Teaching

UN Live: You’ve long championed the idea of the “Collective Journey.” How can story worlds help us practise empathy in a time when society feels increasingly fragmented?

Jeff: In an age of pervasive communication, stories are no longer strictly linear. They can start in one place and then radiate in endless variations to millions in a matter of seconds. Video games, transmedia storyworlds like Star Wars and Minecraft, and particularly social media are multi-perspective, and dialogue-based, comprised of ever-flowing rivers and streams of stories. We need ways to better understand and leverage the way stories have been transformed by technology and mass participation. Collective Journey is my model for describing these complex narratives.

At a time when society feels so fragmented, Collective Journey stories dramatize how we can bridge divides. By shifting emphasis from the defeat of a villain to the repair of a systemic flaw that is negatively impacting the characters’ lives, these stories can provide a means to illustrate paths to transcending conflict, promoting empathy, and fostering reconciliation.

Black Panther is a Collective Journey story, because it highlights the vitality of an Afrofuturist society, showcasing their unique customs and traditions unfettered by colonialism and slavery. But the film also depicts the struggles between different factions within Wakanda contending with their isolationism, reflecting broader themes of unity and division when it comes to dealing with the outside world. This emphasizes the need for collaboration to face common challenges. Each character, even the antagonists, carry a piece of the puzzle. The narrative underscores the idea that true leadership involves listening to community voices—even those that are angry and subversive—and integrating these ideas toward a shared sense of responsibility and greater good.

Photo: Gomez at World Media Summit Bonn

The system in Black Panther is the elite society of Wakanda. The flaw in that system is a fear of loss of abundance, so the leaders of that society choose to close off their borders rather than addressing global inequality, even though they have the capacity to do so. Killmonger, an outsider who has experienced scarcity, appears to be a villain but he is really a catalyst for change (and a trigger for the start of systemic repair) thanks to how he touches and changes T’Challa, the Black Panther. In the end, Wakanda announces itself to the world. This left a powerful impression on global audiences who felt seen, embraced, and lifted by the narrative.

More recently, the Jolly Roger flag from One Piece has been transformed into a symbol of anti-corruption and anti-authoritarian movements among youth worldwide, embodying themes of freedom, unity, and resistance. The Japanese manga (and anime) One Piece is a Collective Journey narrative about the young, optimistic and pure-hearted pirate Monkey D. Luffy and his crew, who seek to unite a vast and varied range of people in the face of a divisive, oppressive, elitist global government. The story is world renowned and provides a strong ethical foundation for its adoption in contemporary activism. As young people continue to seek change and advocate for justice in the real world, the flag serves as a powerful reminder of the collective strength needed to achieve a brighter future.

Even in an increasingly fragmented society, we are still capable of telling stories that resonate with mass culture. Though we are wildly diverse, human beings still have powerful fundamental desires in common. By shifting emphasis from polarized and simplistic conflicts to those that are nuanced, interpersonally dynamic, and built on universal human wisdom, we can better illustrate how we can get over our differences. We can better empathize with one another and focus on fixing what is broken in our systems rather than defeating a villain who will only be replaced by another in the sequel.

UN Live: Popular culture is one of the most influential forces on the planet. What does it take for a narrative to move people from awareness to genuine behavioural change?

Photo: Gomez for BBC Worldwide

Jeff: To effectively generate the momentum needed to move people from awareness to changemaking, we need to dramatize how it’s possible. Our narratives must resonate emotionally, foster a sense of trust and community, and illustrate with clear actions and compelling visuals. We need to showcase individuals engaging in meaningful dialogue. We need to think more deeply about the stories we’re being told and whether or not we believe them.

There is also worldbuilding, which has become popular these days but often can be fanciful and not reflective of our reality in deeper ways. This is why I advocate for creators to develop a “foundational narrative” to their pop culture works. Where are you as the artist in this narrative? How does it reflect your concerns and desires? What crucial questions will it address and perhaps answer? Without the nourishment of subtext, the text is just candy. The audience may enjoy it but then move on unmoved.

And then there is the relatively novel but critical component of audience participation. For the first time since the oral tradition, we as the audience can talk back to the storyteller. In the 21st century, we expect to be acknowledged by the authors or owners of the works we love. It behooves them to validate us by acknowledging our voices and celebrating our participation. If we don’t do this, our audience will simply shrug and look elsewhere for a narrative that does.

By combining these elements, narratives can connect with us personally, inspiring us to transform our awareness into impactful actions, contributing to collective progress and social change.

UN Live: How is this process reflected in your work for social good?

Jeff: My work in causes for social good was inspired by the techniques of Miguel Sabedo, who infused powerful and highly instructive messages into telenovelas in Latin America in the 1960s and ‘70s. These soap operas inspired women to demand education and equal rights for themselves. Norman Lear used these techniques in groundbreaking situation comedies like All in the Family, Good Times, and The Jeffersons, sparking unprecedented national conversations about topics like racism, economic inequality, and domestic abuse. The result over time was a more open and tolerant society.

Personal connection is sparked by sharing relatable and authentic experiences. Characters like Archie Bunker and Florida Evans humanized perspectives that had been marginalized at the time. This approach can be made more direct. Think about those commercials about using seatbelts in cars in the 1970s or about the health risks of smoking in the 1990s. The facts about these dangers existed for many years but huge numbers of people changed their behavior after exposure to advertising campaigns that personalized and conveyed the emotional impact of these risks.

In our crisis work, my team taps into a culture’s deeper mythology. The virtues and values that can be found in their ancient narratives and traditions, often predating contemporary religious beliefs. We discovered that intergenerational trauma such as colonization, war, and slavery push societies out of alignment with these foundational aspirational drivers. Stories that resonate with those mythic narratives but also contain compelling and instructive messaging can help to revitalize an entire people, reminding them of a unified cultural identity, awakening them and strengthening resolve.

Whether these stories emerge synchronistically or by design in a culture, when properly implemented, significant change can occur. What happens next under the right circumstances is spontaneous social self-organization—movements that favor collaboration, connection, and systemic repair. When many are inspired and act in concert, corrupt governments can be challenged, criminal cartels can be made to back down, and the oppressed given a voice. We call this Transmedia Population Activation and have done a good deal of work in this space.

It’s important to note, however, that these powerful narrative tools are subject to abuse. If you remove the inclusiveness of Collective Journey and do things like placing emphasis on othering, declaring entire groups to be subhuman, criminal, or evil, you can generate schisms across a society. When you insist that only a single person can save everyone, your community can abdicate their agency to him. When you foment confusion, raise violence as an immediate solution, or campaign for the diminishment of human sovereignty, you are weaponizing this technique.

The results can give rise to an anxious, fragmented, and polarized people. They can look at the same event in time and space and see two entirely different realities. They will allow for the rise of authoritarianism, suppression of the opposition, a loss of empathy. It is vital that young people be trained to discern how exactly narrative is being communicated to them and what to do if those techniques become corrosive.

UN Live: You often work with communities and fans as co-creators. What have you learned about identity, belonging and emotional connection from the way audiences now inhabit story worlds.

Photo: Gomez in New Zealand

Jeff: Historically, fans were seen as a niche demographic that enjoyed expressing themselves to one another about the content they consumed. In the current landscape, fans have become creators in their own right. They now have the tools and platforms to generate their own content, amplifying their thoughts, and communicate directly with the storytellers. As storytellers, we must recognize that we are no longer broadcasters. Our narratives have become dialogues and our stories have become porous. If we are not mindful of our fans, they can easily express dissatisfaction, corroding our relationship with them. They can turn away from us, leaving our stories to collapse.

Rich and carefully designed storyworlds allow for immersion by the fan. There is so much detail and lore, so many mysteries to be solved, so many character relationships to be explored, the fan wants to stay, see more, collect more, talk about it more. Great storyworlds (whether they be Stranger Things or your favorite sports team) resonate with the experiences of their fans, reflecting their values and desires. We can escape reality in a profound way, because we are also learning. We are seeing our own struggles, triumphs, and identities reflected in these worlds. They foster a sense of belonging.

But it doesn’t end there. Listening is every bit as important as the telling. To be most effective, storytellers need to acknowledge the new relationship between fan and narrative and make certain that an architecture for dialogue is built into this communication. We must validate and celebrate the participation of our audience, inviting them to form communities, express their creativity, fill in the blanks, and foster attachments that can become personally fulfilling. Ask anyone you know. If they are being honest, they will tell you that to be warmly and genuinely heard is the greatest gift they can ever receive.

An example of this that I’m really proud of is how we promoted a fan community in North America for the superhero franchise Ultraman. While the show is made for children in Japan, we found that the richness and complexity of the story world appealed to teens and young adults in the West.

First, we recruited a small number of older fans to help us reach out to this audience. Then we worked to engage this community in formation with messages of genuine enthusiasm. Ultraman’s ethos of courage, hope, and kindness resonated with these fans, who felt their world becoming colder and more callous. The result is a rich tapestry of connection, where fans carry the lessons and themes of these stories into real world experiences, often supporting and uplifting one another. After only a few years there are now millions of Ultraman fans in America.

UN Live: Much of the world’s most grounded relational wisdom comes from Indigenous and non-Western storytelling. What can global storytellers learn from these systems about responsibility and interconnectedness?

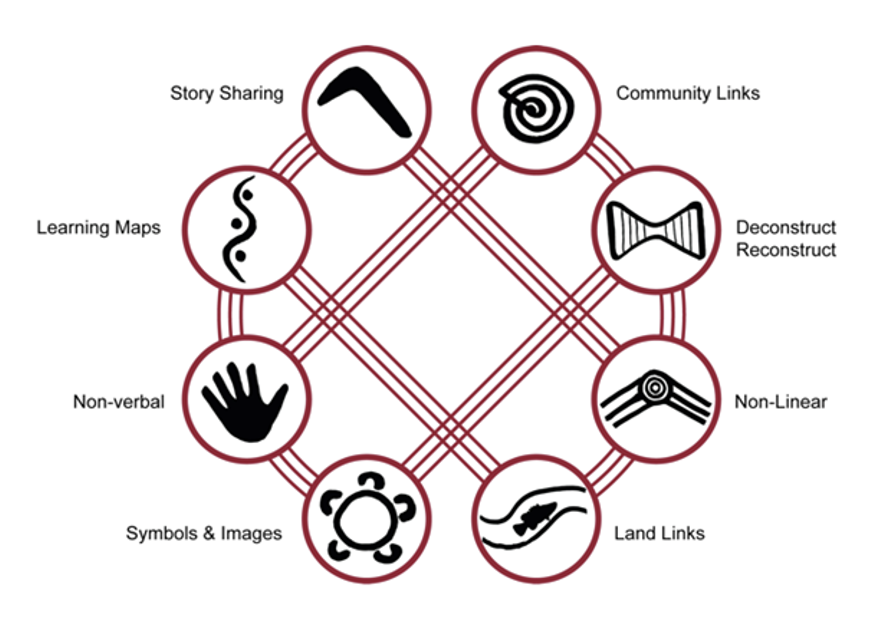

The Indigenous Australian pedagogy and knowledge transmission systems

Jeff: Long before humanity was overwhelmed by materialism, we saw ourselves as deeply ingrained in the natural world. Our sense of self lay comfortably within the context of our surroundings and fundamental needs. Likewise, our wisdom was derived from fellowship, community, story sharing, and the vital relationship we held with our environs.

These insights came to me in a powerful way when I was called to assist in a crisis of education for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in western Australia. Initially, I used standard Western narrative forms to address the crisis but found this approach of little use. What I eventually learned is that First Nations Australians still used a pedagogy of communication and orientation that dated back thousands of years. It was a networked and multimodal approach that allowed for them to survive and thrive in what most of us would experience as a hostile and alien landscape.

Indigenous narratives often prioritize the community as the protagonist, reflecting a holistic view of the world. These storytelling traditions offer alternatives to the Western "A to B" linear progression in favor of ways of being that transcend time and are intrinsic to the environment. They emphasize an approach to wisdom and communication that is nonlinear, utilizes symbols and images, leverages deconstruction and reconstruction (breaking down what they perceive and reinterpreting it in search of answers), and are often nonverbal. All of this sounded to me like the storyscapes we are experiencing on the Internet.

Much of this is echoed in Orphism and the Ancient Hellenic Tradition, which I’ve studied closely, as well as many indigenous wisdoms and philosophical beliefs worldwide. These traditions emphasize interconnectedness, where the community—rather than a lone protagonist—navigates challenges through collaboration and shared purpose. They deeply inform my work in storyworld development, community-building, and Transmedia Population Activation. We use nonlinear narratives (commonly found in video games but now showing up in entertainment franchises and sprawling geopolitical narratives) to reflect the complex nature of reality, allowing for a more inclusive and multi-perspectival understanding of global issues.

Photo: Group photo with Gomez’s Indigenous Australian work

UN Live: If the dominant Western narrative is one of separation, what narrative do you believe we need to practise instead for planetary healing?

Our life-sustaining systems are highly interconnected. If one becomes damaged, the others can be seriously impacted. At the same time, the vast majority of Western narratives celebrate separation. The lone hero is the only one who can save us. Those experiencing scarcity must battle those with abundance. The defeat of a singular villain is favored over systemic change. If we allow these simple binary conflicts to persist, humanity will experience greater suffering.

But there are far too few stories to guide us away from these facile cycles and tropes. The original Avatar, for example, was unique in that it suggested that at least some of our technology can lead to empathy (Jake Sully becomes a Na’vi and connects with Neytiri through use of the Avatar tech) and the interconnectivity of our natural world can unite us against those who would plunder and destroy it. But spectacular as they were, the second and third Avatar films provide the fewest of clues as to how to resolve this dualistic conflict. They offer us no wisdom to reconcile the needs of Earth with those of Pandora. The solutions include only violence; endless, repetitive war.

Narratives that will open our minds, build empathy, and promote planetary healing are ones that shift us from “me” to “we”. They will show us how communities can act as unified forces (as they often do on the internet and in movements that favor inclusive reform) rather than focusing solely on one hero. They will dramatize how different events are linked across time and space, rather than following a narrow “and then” plot structure, to better show us the complexities of causality.

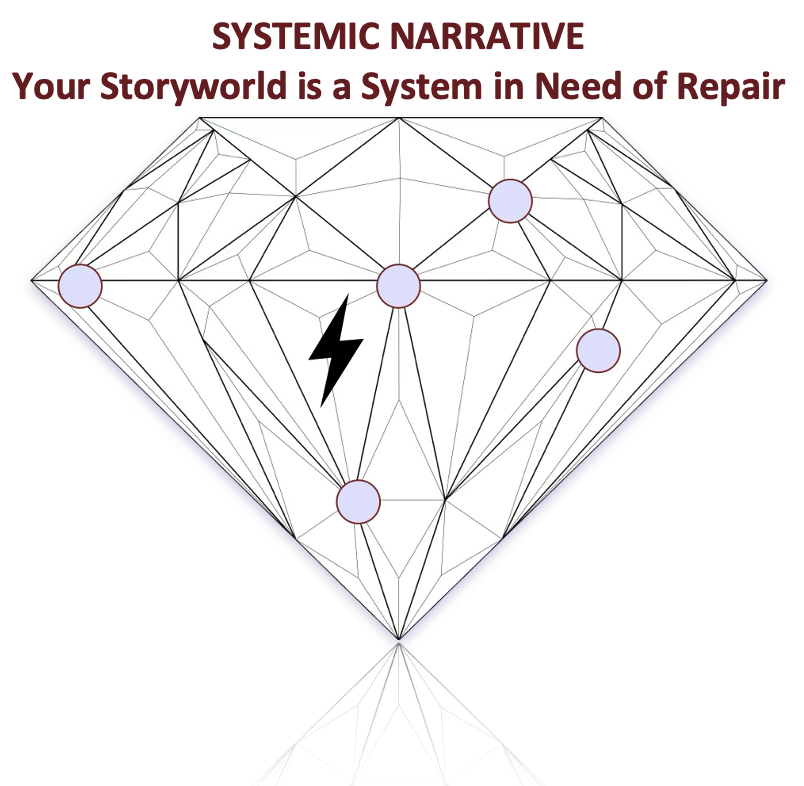

Systemic Narrative

Most importantly, I’m hoping that new storytellers can clearly convey that the worlds of their stories are systems in need of repair. This means that the world of the narrative contains a significant flaw that no one person can fix. In Game of Thrones, for example, Winter is Coming and if it arrives, no one will survive it, not the highest king or lowliest serf. The “game” itself must be set aside—even broken and replaced by something new—for a coalition of characters to do what is needed to set things right.

It will take many perspectives, conflicts, and the juxtaposition of different ideas and approaches to rebuild the systems of these storyworlds, as well as our own. Skilled storytellers will show us how to hold disparate and even opposing viewpoints in our hearts and minds simultaneously—to accept the fact that paradoxes exist—and to make space for circumstance, synchronicity, and the perceptions of ordinary people to introduce solutions for challenges once thought insurmountable.

Finally, our new narratives must teach us how to heal. It’s not enough to defeat one’s enemy without addressing the underlying traumas that caused these behaviors. To avoid repeating these conflicts, we must reconcile, acknowledge the pain that has been inflicted and make amends. The new boss cannot be the same as the old boss.

UN Live: How do you see UN Live helping to shape the stories that bring us closer together?

Jeff: My vision would be for organizations like UN Live to play central roles in organizing ambitious international projects that harnesses the power of storytelling and transmedia narratives to address pressing global issues such as conflict, pollution, poverty, and inequality. These initiatives would bring together diverse coalitions of artists, influencers, corporate leaders, media executives, advertising agencies, national leaders, clergy, educators, and youth to create multi-faceted cultural campaigns that inspire collective action and foster a sense of global community. They would leverage interactive technology to make these unprecedented, dialogue-driven super-narratives that inspire but also build pathways to collective action, momentum gathering, and changemaking.

These super-narratives would be accompanied by international workshops, youth leadership programs, live events, and festivals. But key to all of this would be in pointing our collective finger away from vilifying individuals or even institutions and toward the specific flaws deep within the diamond that comprises our world. Our collective intelligence is now capable of being directed at these flaws and effecting repairs. We can even conceive and give rise to alternate systems resulting in vast improvements. We’ve done this in the past with new kinds of medicine, new forms of energy, and new economic approaches. It’s one thing to theorize these concepts but compelling storytelling can show millions what these theories might be like in action—just as the Communicators and Tricorders of Star Trek inspired Steve Jobs to create iPhones and iPads. To see is to believe.

Under the right circumstances, UN Live can play the role of curator and facilitator, helping to connect various stakeholders, including artists, media executives, and influencers. The organization can provide resources, expertise, and a platform for showcasing the project's outcomes. It can manage campaigns, ensuring that messaging is consistent and impactful across all platforms. The organization can also coordinate with corporate partners to leverage their resources for broader outreach and engagement.

You would need to implement mechanisms to assess the project's impact, gathering data on community engagement, changes in awareness, and actions taken even as the campaign is in flight. This information is vital for refining future initiatives and demonstrating the project’s effectiveness to stakeholders. In keeping with the organization’s core ethos, UN Live's involvement must ensure that the initiative remains focused on empathy, connection, and actionable change. Approaches like this can ultimately contribute to forging a more just and sustainable world.

UN Live: If you could gift humanity one story to carry into the next decade—one that expands our sense of a “Global We”—what would it be?

Jeff: I’m personally concerned. We are on the verge of experiencing a meta-crisis. Our greed, weapons, and thirst for power have made us capable of destroying ourselves by force. Our pollutants and disregard for the fragility of nature have made us capable of destroying our environment. Our technology and irresponsible use of communications have made us capable of destroying our ability to discern reality. This puts us at serious risk. My one story would be about how each of us can use our gifts to respond to this potential cataclysm.

If we have the power of gods, we must strive to achieve the wisdom of gods. The story I envision would be about those of us who can see patterns in the chaos, who understand or learn the values of perseverance and the attainment of mastery. The people who will change the world will need to stand up to enormous challenges. They will have to engage in listening with empathy, warmth and intimacy. They will need to orient themselves at a time where we are bombarded with hardships, facts and fallacies. They must learn to navigate both the planet and cyberspace. They must be conditioned with sensemaking. Most of all, they must commit to accomplishing feats that most would tell them were impossible.

This story of the “Global We” does not have to be a fantasy but it does need to contain enormous imagination. We can’t rely on aliens or superpowers to unite us. This is not a joy ride. There will be heartbreak and suffering. But I would also want to emphasize the power of the adjacent possible. Hopepunk, if you will. It will show us how the human mind is an infinitely versatile tool. How human potential has been proven over and over throughout history. How we are intrinsically woven into—and are nurtured by—the grandeur of the natural world.

As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns us, “there is a danger in a single story," meaning there are no absolute truths about the past. We are capable of holding paradoxes in our hearts and minds. We are capable of transcending trauma and proceeding from a place of love. The shift will happen when we bring all our unique strengths together in service to all humanity and planet Earth.

Photo: Gomez with Madeleine Albright at Aspen Institute

We extend our sincere gratitude to Jeff Gomez for sharing his reflections and insights with us, guiding the conversation on how transmedia narratives can shift us from conflict to collective healing, from "me" to "we," and remind us that the greatest stories provide not just a ladder to climb, but the inspiration to lift ourselves and society together.